|

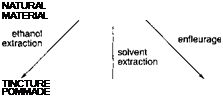

Scheme 3.9 summarizes the various possible processes using solvent extraction to obtain perfume ingredients. The processes are written in lower case and the technical names for the various products in capitals.

![]()

![]()

![]() ethanol

ethanol

extraction

ESSENTIAL OIL

ESSENTIAL OIL

deterpenation

TERPENELESS OIL

Scheme 3.9

Ethanolic extraction is not used very much for plant materials because of the high proportion of water compared with oil in the plant (vanilla beans are an important exception). It is more important with

materials such as ambergris. The sperm whale produces a triterpene known as ambreine in its intestinal tract. This is excreted into the sea and, on exposure to salt water, air and sunlight, undergoes a complex series of degradative reactions which produce the material known as ambergris. (More detail of this chemistry is given in Chapter 4.) This waxy substance can be found floating in the sea or washed up on beaches. Extraction of it with ethanol produces tincture of ambergris.

Enfleurage was used by the ancient Egyptians to extract perfume ingredients from plant material and exudates. Its use continued up to the twentieth century, but it is now of no commercial significance. In enfleurage, the natural material is brought into intimate contact with purified fat. For flowers, for example, the petals are pressed into a thin bed of fat. The perfume oils diffuse into the fat over time and then the fat can be melted and the whole mixture filtered to remove solid matter. On cooling, the fat forms a pommade. Although the pommade contains the odorous principles of the plant, this is not a very convenient form in which to have them. The concentration is relatively low and the fat is not the easiest or most pleasant material to handle, besides which it eventually turns rancid. The ancient Egyptians used to apply the pommade directly to their heads, but in more recent times it became usual to extract the fat with ethanol. The odorous oils are soluble in alcohol because of their degree of oxygenation. The fat used in the extraction and any fats and waxes extracted from the plant along with the oil are insoluble in ethanol and so are separated from the oil. Removal of the ethanol by distillation produces what is known as an absolute.

The most important extraction technique nowadays is simple solvent extraction. The traditional solvent for extraction was benzene, but this has been superseded by other solvents because of concern over the possible toxic effects of benzene on those working with it. Petroleum ether, acetone, hexane and ethyl acetate, together with various combinations of these, are typical solvents used for extraction. Recently, there has been a great deal of interest in the use of carbon dioxide as an extraction solvent. The process is normally referred to as super-critical carbon dioxide extraction but, in fact, the pressures employed are usually below the critical pressure and the extraction medium is subcritical, liquid carbon dioxide. The pressure required to liquefy carbon dioxide at ambient temperature is still considerable and thus the necessary equipment is expensive. This is reflected in the cost of the oils produced, but carbon dioxide has the advantage that it is easily removed and there are no concerns about residual solvent levels.

The product of such extractions is called a concrete or resinoid. It can be extracted with ethanol to yield an absolute, or distilled to give an essential oil. The oil can then be deterpenated. As noted earlier, the use of the word terpene here is misleading to the chemist since, in this instance, it refers specifically to monoterpene hydrocarbons. Hence, a terpeneless oil is one from which the hydrocarbons have been removed to leave only the oxygenated species and so increase the strength of its odour. With some particularly viscous concretes, such as those from treemoss or oakmoss, it is more usual to dissolve the concrete in a high boiling solvent, such as bis-2-ethylhexyl phthalate, and then co-distil the product with this solvent.

Essential oils and other extracts vary considerably in price and in the volume used each year. Lavender, for example, is a relatively inexpensive oil, costing £15-20/kg and 250-300 tonnes are used annually. Rose and jasmine are much more expensive and are used in much smaller quantities. The total annual production of rose oil is 15-20 tonnes and it costs between £1000 and £3000/kg, depending on quality. About 12 tonnes of jasmine extracts are produced annually at prices up to £2000/kg. Eucalyptus oil (from Eucalyptus globulus) has one of the largest production volumes, almost 2000 tonnes/annum and is one of the cheapest oils at £2-3/kg. The exact balance between volume and price depends on various factors such as ease of cultivation, ease of extraction and usefulness. For example, eucalyptus trees grow well, the leaves are easy to harvest, trimmed trees grow back vigorously, the oil is easily distilled and it is useful as a disinfectant as well as a camphor — aceous fragrance ingredient. All of these factors combine to make it a high-tonnage oil.

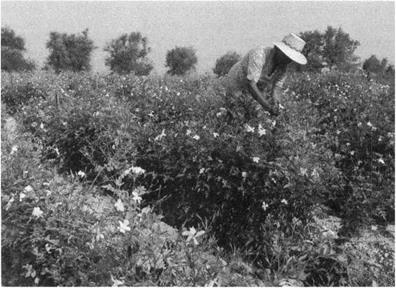

Before this century, perfumes commanded such a price that only the wealthiest people could afford them. This is because perfumers relied on natural sources for their ingredients. Most of these ingredients are in limited supply and are expensive to produce. For instance, it takes about 7 000 000 jasmine flowers to produce 1 kg of oil. The flowers have to be picked by hand (no-one has yet devised a mechanical method of harvesting jasmine) in the first few hours of the day when their oil content is at its highest (Figure 3.3). In view of the costs of cultivation and extraction, it is not surprising to find that jasmine oils cost in the region of £2000/kg.

Some natural oils are much less expensive because of automated farming methods. For instance, rows of lavender in a field (Figure 3.4) can be cut almost to ground level and fed directly into a still pot carried on the tractor. The pot is then fitted under a field still and the oil extracted while the harvesting continues. The cost of lavender oil is thus tens, rather than thousands, of pounds per kilogramme. Despite this,

|

Figure 3.3 Hand picking of jasmine |

|

Figure 3.4 Cultivation of lavender |

the modern perfumery industry would be unable to function as it does if it were to rely solely on natural ingredients. Cost alone would be prohibitive, regardless of problems of stability in products or availability in view of limits on land use, etc.

Since essential oils are usually present in the botanical source at the level of only a percent or two, at most, of the dry weight of the harvested plant, it is more economic to extract the oil at the location where the plant grows, and ship the oil rather than the plant material, to the customer. The degree of sophistication of the harvesting and extraction technology varies widely, depending on the country of origin. The mint production of the USA and the lavender production of Tasmania are highly automated; indeed, they must be to remain economically feasible in countries with such high labour costs. In some other countries, simple bush stills constructed from waste oil drums and drainpipes are the most cost-effective means of production. Table 3.2 lists some of the more important of the essential oils used in perfumery today, and includes information on the plant parts and extraction techniques used to produce the fragrance products and also some of the more important countries of origin for each.

27 июня, 2015

27 июня, 2015  Malyar

Malyar

Опубликовано в рубрике

Опубликовано в рубрике