In Exodus, God gives Moses instructions for a holy perfume for himself, and a different one for his priests, whilst the Queen of Sheba’s visit to Solomon was motivated by her wish to keep open the trade routes of the Arabian peninsula, her source of frankincense and myrrh, through Palestine to Egypt and Mesopotamia.

The story of Jesus of Nazareth is populated by fragrant materials, from frankincense and myrrh, his gifts at birth, through to the use of spikenard to wash his feet during life and finally the use of myrrh in the binding sheets of his body after crucifixion. Through trade and cultivation, Palestine became a great source of aromatic wealth, and a key trade route for myrrh and frankincense.

The Greeks further developed the use of fragrances, not only in praise of their Gods, but also for purely hedonistic purposes and for use in exercises and games, the first beginnings of early forms of aromatherapy. Their myths are full of references to aromas. Tear-shaped drops of the resin myrrh were the tears of a girl transmuted into a tree by the Gods. The hyacinth flower grew from the blood of dying Hyacinthus, struck by a discus during a feud between two other Gods. The iris grew at the end of a rainbow, whilst the narcissus flower grew at the spot near a mountain pool, where its erstwhile namesake drowned. Whilst a special fragrance formulation for the Goddess Aphrodite created such sensual desire that the term ‘aphrodisiac’ was used in its praise.

The sciences of medicine and herbalism developed with Hippocrates and Theophrastus, whilst Alexander the Great, tutored by Aristotle, conquered half the known world, acquiring a love of fragrance from the defeated Persian kings. But it was Aristotle who, in the third century вс, arguably advanced the cause of alchemy. It was he who observed the production of pure water from the evaporation of seawater. He

|

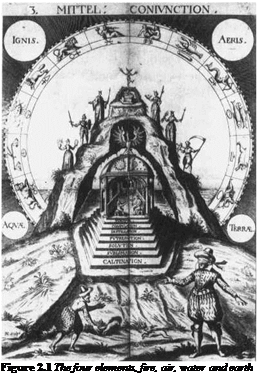

translated the Book of Hermes, written by an Arab, Al-Makim. It expounded the theory, first suggested by Empedocles around 450bc, that all substances are made of the four elements, fire, earth, air and water (Figure 2.1). By varying the amounts of the different elements in each compound, all other elements could be made.

The theory developed further to discuss moods related to the elements and the seasons, as illustrated in Figure 2.2. The four key moods described were phlegmatic (solid, calm, unexcitable),

|

Wet |

Spring |

Cold |

Winter |

|

Air |

Sanguine |

Water |

Phlegmatic |

|

Figure 2.2 Elements and moods |

choleric (irascible, hot-tempered), sanguine (optimistic, confident) and melancholic (sad, pensive). Combinations of the four moods at their boundaries give eight mood poles, and it is around these that some modern-day theories of aromatherapy have evolved.

The most used fragrances of the Greeks were rose, saffron, frankincense, myrrh, violets, spikenard, cinnamon and cedarwood, and to obtain these aromatics they traded far and wide throughout the Mediterranean and Middle East.

Meanwhile, in Rome, Pliny the Elder outlined a primitive method of condensation which collected oil from rosin on a bed of wool, and also made the first tentative experiments in chromatography. The Romans had developed techniques of enamelling, and made one of the most fundamental discoveries: that glass could be blown. The Roman contribution to perfumes consisted mainly in making an industry of the supply of raw materials and production of a large variety of fragrances in different forms. Military conquests secured new sources and supply routes to fit the steady demands of a far-flung empire, and the key products in demand were:

—Hedysmata: solid unguents, normally in the form of gums and resins;

—Stymata: liquid toilet waters infused with flower petals;

—Diapasmata: powdered perfumes using aromatics disposed in talc or gypsum.

Roman elite kept Acerra, small incense caskets, in their homes, and carried ampullae, perfume containers, and strigils, wooden blades for scraping oils off the skin at the hot baths. Petronius wrote:

19 июня, 2015

19 июня, 2015  Malyar

Malyar  Опубликовано в рубрике

Опубликовано в рубрике