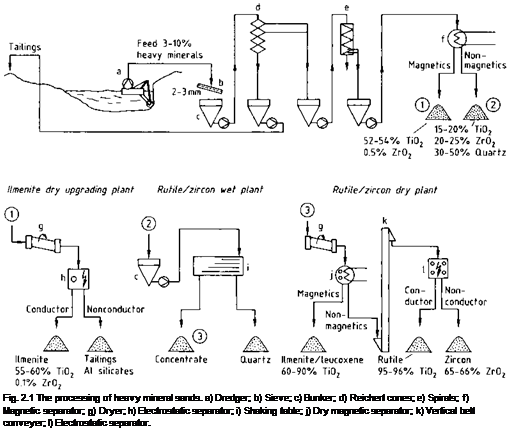

Most of the world’s titanium ore production starts from heavy mineral sands. Figure

2.1 shows a scheme of the production process. The ilmenite is usually associated with rutile and zircon, so that ilmenite production is linked to the recovery of these minerals. If geological and hydrological conditions permit, the raw sand (usually containing 3-10% heavy minerals) is obtained by wet dredging (a). After a sieve test (b), the raw sand is subjected to gravity concentration in several stages with Reichert cones (d) and/or spirals (e) to give a product containing 90-98% heavy minerals. This equipment separates the heavy minerals from the light ones (densities: 4.2-4.8 g cm-3 and <3 g cm-3 respectively) [2.12].

The magnetic minerals (ilmenite) are then separated from the nonmagnetic (rutile, zircon, and silicates) by dry or wet magnetic separation (f). If the ores are from unweathered deposits, the magnetite must first be removed. An electrostatic separation stage (h) allows separation of harmful nonconducting mineral impurities such as granite, silicates, and phosphates from the ilmenite, which is a good conductor. The nonmagnetic fraction (leucoxene, rutile, and zircon) then experiences further hydromechanical processing (i) (shaking table, spirals) to remove the remaining low-density minerals (mostly quartz). Recovery of the weakly magnetic weathered ilmenites and leucoxenes is by high-intensity magnetic separation (j) in a final dry stage. The conducting rutile is then separated from the nonconducting zircon electrostatically in several stages (l). Residual quartz is removed by an air blast.

|

2.1.2.2

18 сентября, 2015

18 сентября, 2015  Pokraskin

Pokraskin  Опубликовано в рубрике

Опубликовано в рубрике