Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is now well established as one of the most useful instrumental techniques for characterization of adhesives and for the study of polymeric adhesive structure-property relationships [34]. The reasons are that (1) individual chemical groups in adhesive often give signals that can be resolved, (2) the NMR signals are sensitive to environment, and (3) the theory is well understood and the relationship between spectral parameters and the information of interest (such as concentration or structure) is relatively straightforward. Polymer scientists and technologists have been

|

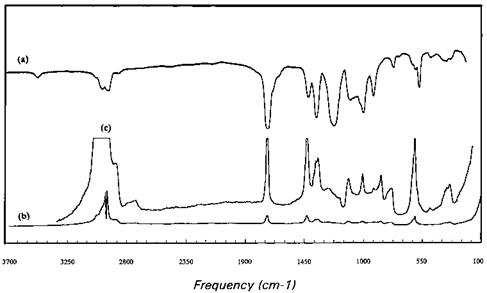

Figure 13 (a) Infrared and (b) Raman spectra of poly(vinyl acetate). (c) The expansion of (b). |

using NMR to study the detailed chain structure of polymers and copolymers and the morphology and transition in the solid state. It has also provided a means for identifying intermediate structures formed during polymerization reactions so permitting more detailed reaction mechanisms to be proposed.

Nuclear magnetic resonance involves the interaction of radio waves and the spinning nuclei of the combined atoms in a molecule. The nuclei of certain isotopes, such as 1H, 19F, P, C, N, Si, and others have an intrinsic spinning motion around their axes, which generates a magnetic moment along the axis of spin.

For the vast majority of polymeric materials, only 1H exists in high concentration and it has been the subject of the majority of applications of NMR to date. However, recent advances in instrumentation and computer capabilities, coupled with pulse techniques and Fourier transformation, have greatly enhanced the sensitivity of NMR spectroscopy. Thus, NMR spectra may be obtained from solutions of very low concentration, nuclei may be observed that have very low natural abundance (i. e., 19F, 31P, 13C, 15N, 29Si), and resolution of spectral lines is greatly improved. Until recently, high-resolution NMR spectra could be obtained only on samples in solution; however, new spectrometers have become available which utilize special techniques to provide solid-sample capability [35,36].

The simultaneous application of a strong external magnetic field Ho, and the radiation from a second and weaker radio-frequency source H1 (applied perpendicular to Ho) to the nuclei results in transitions between energy states of the nuclear spin. The NMR phenomenon occurs when these nuclei undergo transition from one alignment in the applied field to an opposite one. This process is illustrated in Fig. 14 for a hydrogen nucleus.

The energy absorption is a quantized process, and the energy absorbed must equal the energy difference between the two states involved:

^absorbed = (E-1/2 state — £+V2 state) = hv (11)

In practice, this energy difference is a function of the strength of the applied magnetic field, Ho. The relationship between these energy levels and the frequency v of absorbed radiation can be calculated as follows:

E =-M(j ІР) B (12)

where M is the magnetic quantum number, m the nuclear magnetic spin, Bo the applied magnetic field, and I the spin angular momentum.

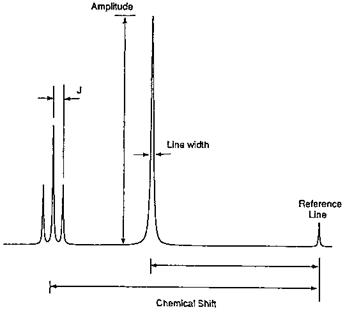

At a given radio frequency, all protons absorb at the same effective field strength, but they absorb at different applied field strengths. It is this applied field strength that is measured and against which the absorption is plotted. The NMR spectrum consists of a set of resonances (or spectral lines) corresponding to the different types of hydrogen atoms in the sample. There are six basic measurements that can be obtained from a set of resonances: (1) the number of signals, which is related to the number of protons presented in the molecule; (2) the intensity or area under the resonance, which is proportional to the amount of species present in the sample; (3) the position of the resonance or chemical shift, which is indicative of the identity of the species; (4) the line width of the resonance, which is related to the molecular environment of the particular 1H; (5) the multiplet structure, which is related to the spin-spin coupling constant (J); and (6) a relaxation time (T2) which is related to the line width. These parameters used in adhesive characterization are shown in Fig. 15. The fact that the resonance area is proportional to the concentration of the

|

Figure 15 A NMR signal is characterized by several parameters: number of signals; intensity or amplitude; line width; multiplet structure and coupling constant, J; and chemical shift. |

species is the basis of quantitative NMR. By taking the ratios of different resonances corresponding to different species, the composition of multicomponent systems can be obtained.

In a given molecule, protons with the same environment absorb at the same applied field strength; protons with different environments absorb at different field strengths. A set of protons with the same environment is considered to be equivalent; the number of signals in the NMR spectrum shows how many sets of equivalent protons a molecule contains. The position of the signals in the spectrum indicates the types of protons (primary, secondary, tertiary, aromatic, benzylic, acetylenic, vinylic, etc.) in the molecule. These protons of different kinds have different electronic environments, which determine the number and location of the signals generated. When a molecule is placed in a magnetic field, circulation of electrons about the proton itself generates a field that acts against or reinforces the applied field. In each situation, the proton is to be shielded or deshielded. Shielding or deshielding thus shift the absorption upfield and downfield, respectively. For example, the proton attached to the carbonyl carbon of acetaldehyde (CH3-CHO) is more deshielded, due to the electron-withdrawing properties of the carbonyl oxygen, than the protons of the methyl group of an alkane (R-CH3), which are surrounded by a higher electron density since there is no electron-withdrawing group. The carbonyl proton absorbs downfield from the methyl protons. The reference point from which chemical shifts are measured is not the signal from a naked proton, but the signal from a reference compound, usually tetramethylsilane, (CH3)4Si (TMS).

The position of the absorption relative to TMS is called the chemical shift; its designation is 8 and its units are ppm (parts per million). Thus

chemical shift from TMS (Hz) ,

chemical shift (ppm) =————————————————————— — x 106 (13)

spectrometer frequency (Hz)

For protons there is an alternative scale that expresses the chemical shifts in ppm on a t (tau) scale, so that

t = 10 — 8 (14)

Most chemical shifts have 8 values between 0 and 15. A small 8 value represents a small downfield shift, and vice versa. A simplified correlation chart for proton chemical shift values is shown in Table 2 [37].

The real power of NMR derives from its ability to define complete sequences of groups or arrangements of atoms in the molecule. The absorption band multiplicities (splitting patterns) give the spatial positions of the nuclei. These splitting patterns arise through reciprocal magnetic interaction between spinning nuclei in a molecular system facilitated by the strongly magnetic binding electrons of the molecule in the intervening bonds. This coupling, called spin-spin coupling or splitting, causes mutual splitting of the otherwise sharp resonance lines into multiplets. The strength of the spin-spin coupling or coupling constant, denoted by J, is given by the spacings between the individual lines of the multiplets. The number of splittings of a multiplet adjacent to n equivalent spins is given by

s = 2nl + 1 (15)

where s is the number of lines and I is the spin of the nucleus causing the splitting. Since 1H has a spin of 1/2, this reduces to n+1 for proton spectra. The intensities of the multiplets also have a predictable ratio and turn out to be related to the coefficients of the binomial expansion (a+b)n. These are given by Pascal’s triangle, where each coefficient is the sum of the two terms diagonally above it (Table 3). For simple spectra, then, we can predict the

2.7

![]() -C-CH2-O-R 3.4

-C-CH2-O-R 3.4

3.0 — CH2-Cl 3.4

3.3 — CH2-Br 3.4

3.8 — C-CH2-O-H 3.6

3.7 — C-CH2-O-CO-R 4.1

-C-CH2-O-Ar 4.3

-C-CH2-NO2 4.4

R = Alkyl group; Ar = Aromatic group. Source: Ref. 37.

![]() Copyright © 2003 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

Copyright © 2003 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

|

n |

Multiplicity |

Intensity |

|

0 |

singlet |

1 |

|

1 |

doublet |

11 |

|

2 |

triplet |

1 2 1 |

|

3 |

quartet |

1331 |

|

4 |

quintet |

1 4 6 4 1 |

|

5 |

sextet |

1 5 10 10 5 1 |

number of splittings and their intensities from the multiplicity and intensity rules given above.

An NMR instrument normally has a strong magnet with a homogeneous field, a radio-frequency transmitter and receiver, and a computer to store, compile, and integrate the signals. A sample holder positions the sample relative to the magnetic field so that the sample will be exposed continously to a homogeneous magnetic field. The sample holder may also have a variable temperature control. Instruments for NMR are built with different magnetic field strengths. They are listed according to the radio frequencies required for the proton to resonate. They can have magnetic fields that require protons to absorb from 60 to 600 MHz to resonate.

A few words about sample preparation. The typical NMR spectrum is obtained from a sample in a 5-mm thin-walled glass tube containing about 0.4 mL of sample. Sample concentrations for routine work can be as low as 0.01 M, but concentrations greater than 0.2 M are preferred for good signal-to-noise ratio. Liquid samples are seldom run as neat liquids, since their greater viscosity will lead to broader lines. Instead, the liquids and solids are dissolved in a suitable solvent that does not show any peaks in the region of interest. Common solvents include CCl4, CDCl3, D2O, acetone-d6, and DMSO-d6.

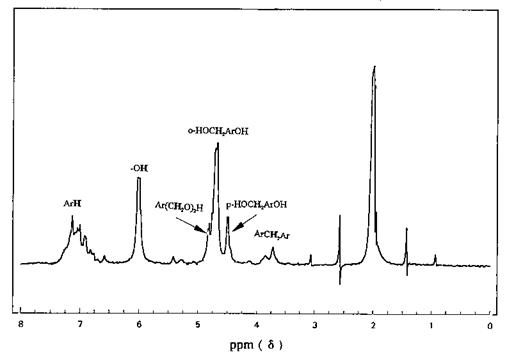

Many studies have been done for polymer systems with respect to monomer composition and the average stereochemical configuration present along polymeric chains [38,39]. Both solid-state and conventional solution NMR techniques provide information on molecular motion, chain flexibility, and in some cases, crystallinity and network formation due to chain entanglement or cross-links [40-42]. The use of NMR spectroscopy for solid polymers has been reviewed by McBrierty [43-45], who has covered molecular motion studies in addition to the structural characterization of these systems in great detail. Jelinski [46] addressed the subject of chemical information and problem solving for both solution and solid-state polymer studies. In addition to elucidating chemical structure, NMR can also be used for a particular facet of a structure, such as chain length or number of moles of a branched polymer, and in the study of polymer motion by relaxation measurements. Kinetic studies of curing reactions at temperatures in the range —150 to +200°C are another application. Useful information can also be obtained from complex mixtures, such as the total methylene linkage of a PF adhesive. The NMR technique has also been used to distinguish the structure of transient molecules involved in resin formation [47], structures of species involved in HMTA cure, and the final structure of phenolic oligomers [48]. Figure 16 is the NMR spectrum of a PF resol in acetone-d6 solution. The resonances of the protons in various structures are identified.

As mentioned earlier, one of the low-sensitivity nuclei which has become a routine analytical tool for polymer chemists since the advent of Fourier transform NMR is 13C.

|

Figure 16 The NMR spectrum of a phenol-formaldehyde (resol) adhesive. |

The magnetic moment of 13C is about one quarter of that of [5]H, but its natural abundance is only 1.1%. The rare occurrence of the isotope greatly simplifies 13C NMR spectra by eliminating the spin-spin coupling (13C-13C) which is so dominant in 1H NMR spectra. The other advantage of 13C NMR is that the chemical shifts are dispersed over 200 ppm rather than the 10 ppm typically observed for 1H NMR. A 13C NMR spectrum of a reaction mixture of UF concentrate with phenol under acidic conditions is shown in Fig. 17, in which the presence of co-condensed methylene carbon was confirmed.

10 июля, 2015

10 июля, 2015  Malyar

Malyar

Опубликовано в рубрике

Опубликовано в рубрике