I found the place in which they touched to become absolutely transparent, as if they had there been one continued piece

of glass

Isaac Newton,1 Opticks, p. 194

The ideas that Newton developed about the sticking together of bodies were quite advanced compared with those of Galileo who had died just a few years earlier. Although Galileo,2 from his observations of the planets, had come to the conclusion that “all parts of the Earth do congregate… ever striving… at union”, and thus had a vision of adhesion as a general property of matter, he had only produced a vague and shadowy theory of this notion. He speculated that there were two causes: one was the abhorrence that nature had for the vacuum created as bodies were separated; the other was the viscous resistance needed to deform the materials. Galileo was wrong on both these matters.

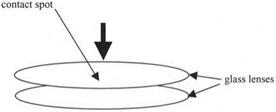

In contrast, Newton pressed glass lenses together and considered that the fundamental particles of the glass should become intimately bonded at the transparent contact area (see Fig. 3.1). He found adhesion in some cases. From the observations, he could address the common fallacies of the time, including the idea that vacuum was necessary, and the other common notions that the bodies require glue or have to key together to produce an adhesive effect. Let us consider these fallacies first before going on to state the laws that follow from Newton’s logic.

|

|

|

|

5 сентября, 2015

5 сентября, 2015  Pokraskin

Pokraskin

Опубликовано в рубрике

Опубликовано в рубрике