The joint design is fundamental to the integrity and efficacy of the performance of the adhesive. Some detailed notes on joint design are given in Chapter 5, but it is important to try and understand all the forces that the adhesive is being subjected to. In practice, this means that the nature and magnitude of the stresses expected during the working life of the assembly must be understood before deciding on the type of adhesive that should be used.

If the force acts in one direction over a long period of time, it can result in the phenomenon of creep. This leads to a slow, but constant, relative displacement of the bonded components. This displacement progresses until the adhesive bond fails. The creep represents a material behaviour exhibited not only by plastic materials and adhesives, but also by metals (although less noticeably). The crosslinked thermosetting adhesives (e. g., epoxies) generally have a higher resistance to creep than the thermoplastic adhesives such as cyanoacrylates. Correct design of the assembly can prevent this phenomenon from appearing or at least reduce it to allowable limits.

|

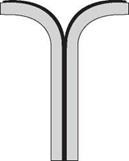

Figure 7.1 Peel forces should be avoided |

From a design viewpoint, every application will be different and so considered

independently but some important guidelines are as follows:

• Always use the largest possible area and align the joints such that stresses can be absorbed in the direction of greatest bond strength.

• Maximise shear forces and minimise peel and cleavage forces (Figure 7.1).

• For most applications, the gap between the parts should be thin (<0.15 mm) but sometimes a thicker bond line can be beneficial for impact loading or where the adhesive is required to absorb stresses due to differing coefficients of thermal expansion.

• Slightly rougher surfaces are usually beneficial and oils, mould release agents and other surface contaminants should be avoided.

28 ноября, 2015

28 ноября, 2015  Pokraskin

Pokraskin

Опубликовано в рубрике

Опубликовано в рубрике