The butt joint can be in various configurations (Figure 5.19) and this is almost certainly the easiest and lowest-cost joint. The success of this joint will depend on the materials bonded, the loads on the joint and the thicknesses of the substrates involved.

If the adherends are rigid and a moment or offset load is applied to this joint then the adhesive will be subjected to quite a severe cleavage or peel load (Figure 5.20) and as such the butt joint is generally regarded as a poor joint design.

In some applications the butt joint may be the only possible method of assembling the component parts and, if aesthetics are important, the small fillet of excess adhesive outside the joint (which adds to the strength of the joint) may also be undesirable. One example of this in the plastics industry is the assembly of shelving where acrylic or polycarbonate sheets are bonded together to form ‘points of sale’ display equipment.

Figure 5.18 For blind holes, apply the adhesive to the base of the hole

I

/

|

Figure 5.20 An offset tensile load or a moment can create high cleavage or peel loads in the joint line |

|

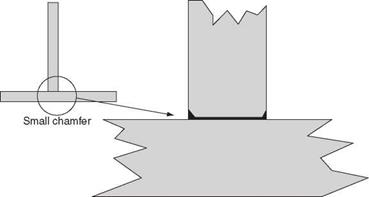

Figure 5.21 A small chamfer will increase the strength of the joint |

In these cases a small internal chamfer can help to improve the integrity and aesthetics of the joint and it allows for some tolerance on the dispensed quantity of adhesive (Figure 5.21) as it can be quite difficult to dispense the exact quantity of adhesive so that it stops exactly at the edge of the joint. The chamfer creates a small gap to allow for the adhesive flow.

In these applications a variety of adhesives are used including UV cure, cyanoacrylates and two-part adhesives (epoxies or acrylics) and the adhesive is selected for its clarity, cost, speed of cure and ease of use.

3 ноября, 2015

3 ноября, 2015  Pokraskin

Pokraskin

Опубликовано в рубрике

Опубликовано в рубрике